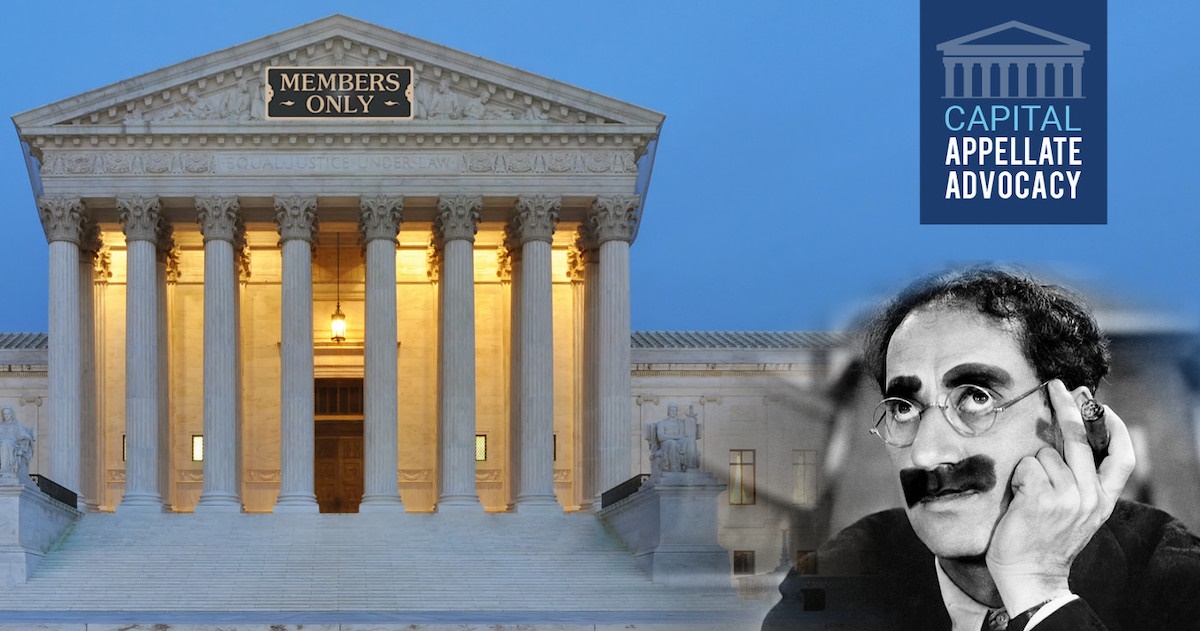

Groucho Marx famously said “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as a member.” Unlike Groucho’s club, the Supreme Court Bar is a “club” in which a multitude of talented appellate lawyers throughout the United States—not just an elite handful of marquee players—can be, should be, and in fact are, active participants.

What is “the Supreme Court Bar”?

During the past 15 years, three widely read articles, bolstered by starstruck legal media, have helped foster the perception that there is a newly emergent “Supreme Court Bar.” Excluding the vast majority of Supreme Court practitioners, they define “the Supreme Court Bar” as a small, elite group of mostly Washington, D.C.-based attorneys who received their law degrees from top-tier schools, clerked at the Supreme Court and/or served in the Office of the Solicitor General, and repeatedly participate in oral arguments before nine welcoming Justices.

Three widely read articles, and starstruck legal media, have created the perception that “the Supreme Court Bar” is composed of a handful of elite lawyers.

Although there are others, these are the three influential articles that I have in mind:

“Better advocacy”

In 2004, Professor Richard J. Lazarus, then Director of the Supreme Court Institute at Georgetown University Law Center, published a law review article discussing “the emergence of a new elite Supreme Court Bar and the resulting transformation of the Court, its plenary docket, and its rulings.” Richard J. Lazarus, Advocacy Matters Before and Within the Supreme Court: Transforming the Court by Transforming the Bar, 96 Geo. L.J. 1487, 1490 (2004).

According to the Lazarus article, the “re-emergence of a Supreme Court Bar of elite attorneys similar to the early-nineteenth-century Bar in its domination of Supreme Court advocacy” has produced “better advocacy before the Court,” and in the case of Chief Justice Roberts (who had been one of those elite attorneys while in private practice), “better advocacy within the Court.” Id.

The article uses the word “elite” 13 times, and various forms of “dominate” 20 times.

“The elite of the elite”

In 2014, The Echo Chamber, a Reuters Special Report, asserted that “an elite cadre of lawyers”—“66 of the 17,000 lawyers who petitioned the Supreme Court” during a nine-year period” —“succeeded at getting their clients’ appeals heard at a remarkable rate,” thereby “giving their clients a disproportionate chance of influencing the law of the land.”

The 47-page report, authored primarily by Joan Biskupic and replete with statistics, describes this “elite bar” as “the elite of the elite.” Just in case readers miss the point, the article repeats the word “elite” at least 25 more times.

The report notes that “some legal experts contend that the reliance on a small cluster of specialists, most working on behalf of businesses, has turned the Supreme Court into an echo chamber – a place where an elite group of jurists embraces an elite group of lawyers who reinforce narrow views of how the law should be construed.”

The “amicus machine”

In 2016, Professors Allison Orr Larsen and Neal Devins of The College of William and Mary School of Law authored a law review article describing what they call the Supreme Court “amicus machine.” Allison Orr Larsen & Neal Devins, The Amicus Machine, 102 Va. L. Rev. 1901 (2016).

The authors explain that the amicus machine is a “systematic, choreographed engine designed by people in the know to get the Justices the information they crave, packaged by lawyers they trust.” Id. at 1915. According to the article, the amicus machine was devised and is operated by, “a private Supreme Court Bar of elites”—“a select group of fewer than 100 lawyers who are repeat players at the Court.” Id. at 1916. The article explains that in a given case, the members of this pro-business “club of elites” either solicit or prepare a set of “orchestrated” amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs which boost the chances that review will be granted. Id. at 1904, 1940.

According to the article, which uses the word “elite” almost 30 times, “the identity of the lawyer on the amicus brief matters.” Id. at 1937. The article also argues that “the Justices and the members of the Supreme Court Bar both benefit from a system that incentivizes the filing of high-quality briefs by Supreme Court specialists.” Id. at 1907. The authors contend that “[i]f the amicus boom is going to continue, it is better monitored by a set of repeat players and specialists than left to grow wildly on its own.” Id. at 1965-66.

A broader, more realistic, and better definition of the Supreme Court Bar

Without question, practice before the Supreme Court of the United States is an area of specialization that should be reserved for experienced appellate attorneys. Approximately 300,000 attorneys, some only a few years out of law school, have submitted the application and paid the $200 fee to “join” the Supreme Court Bar and obtain an impressive certificate to hang on their walls. That alone clearly is not enough to make a lawyer qualified to practice before the Court.

On the other hand, there is no reason why Supreme Court practice should be limited to, or dominated by, the type of small, elite, insular, “bar” discussed in the three articles cited above. Professor Lazarus defines “an expert Supreme Court advocate” as “someone who has either . . . presented at least five oral arguments before the Court or works with a law firm or other organization with attorneys who in the aggregate have presented a total of at least ten arguments before the Court.” Lazarus, supra at 1490 n.17. There can be no doubt that most highly experienced Supreme Court oralists should be viewed as expert Supreme Court advocates, and no criticism of those very talented attorneys is intended.

Supreme Court practice should not be restricted to, or dominated by, a small, elite, insular “bar.”

In my view, however, membership in “the Supreme Court Bar” should not be restricted to attorneys who have substantial stand-up experience before the Court. Instead, there are hundreds of appellate specialists throughout the United States who are well qualified to handle the vast majority of Supreme Court work, which is in written form. Given the tiny percentage of cases that the Court agrees to hear, Supreme Court practice—in reality— primarily involves the drafting of certiorari petitions, briefs in opposition, and petition-stage amicus briefs. And where certiorari has been granted, Supreme Court practice focuses on the drafting of merits briefs and merits-stage amicus briefs, as well as oral argument.

The vast majority of Supreme Court practice is in written form. Drafting Supreme Court petitions and briefs is an art that any talented appellate attorney can master through hard work and experience.

In addition to understanding the Supreme Court’s rules, and appreciating the types of issues and cases that the Court agrees—and does not agree—to hear, every Supreme Court practitioner needs well-honed strategic, analytical, and brief-writing skills. Of course, there is an art to drafting effective Supreme Court petitions and briefs, beginning with the way that the questions presented are articulated. It is an acquired art, which I believe any talented appellate attorney can learn through experience, regardless of whether he or she has a law degree from a top-tier law school, was a Supreme Court law clerk, or served in the Solicitor General’s office.

Furthermore, a large variety of self-confident, well-prepared appellate specialists from around the nation demonstrate almost every hearing day that they are capable of superb oral advocacy, which at the Supreme Court is more conversational than rhetorical.

The real, larger and more diverse, Supreme Court Bar

What about the statistics suggesting that Supreme Court petitioners do better when represented by a name-brand Supreme Court advocate, i.e., by a member of the “new elite Supreme Court Bar”? Insofar as that is true, should every private-party Supreme Court litigant with very substantial financial resources engage one of the “elite of the elite” (along with the tiers of more junior attorneys who actually do most of the research and drafting)? And what about litigants that can’t afford to pay astronomical legal fees?

In my opinion, hiring a superstar Supreme Court generalist when a case is appealed to the Court may not always be the key to success, including in cases where review is granted. For example, a well-qualified but lesser-known appellate attorney who has spent years handling a case, or addressing a legal issue, in the lower appellate courts may have much deeper substantive expertise, a better understanding of the questions presented and their nuances, and more extensive knowledge of the evidentiary record. If such an attorney also has mastered the art of drafting Supreme Court petitions and briefs, and can handle the Justices’ questions at oral argument with aplomb, is it really more desirable to relegate that attorney to a supporting role?

The perception that “the Supreme Court Bar” is, and should be, an elite, self-perpetuating echo chamber needs to be changed.

More broadly, the perception that “the Supreme Court Bar” is, and should continue to be, an elite, tight-knit, self-perpetuating “echo chamber” should be changed. In my view, it is better for the practicing Supreme Court Bar to be considerably larger and more diverse than a “club of elites.” It should be composed of many skilled appellate advocates from around the United States who bring differing perspectives, a variety of brief-writing and oral advocacy talents, and substantive expertise and experience to the Court. Indeed, this aptly describes what already is the real Supreme Court Bar—a reality that the Justices of the Supreme Court, along with law school professors and legal media, not only should embrace, but also laud.

The real Supreme Court Bar encompasses many skilled appellate advocates from around the United States who bring to the Court differing perspectives, a variety of brief-writing and oral advocacy talents, and substantive expertise and experience.

Note: A version of this article, under the title “A Broader View of the US Supreme Court Bar,” was published by Law360 on April 24, 2019 and reprinted with permission in the July 2019 edition of DRI’s For The Defense magazine.